六分钟步行试验作为一种功能锻炼能力测量方式的历史进展:叙述性综述

引言

功能能力是一个人进行日常生活活动的能力,如步行、洗澡或来回走动,客观量化为最大努力心肺运动试验(cardiopulmonary exercise test,CPET)[1,2]期间的最大耗氧量(maximal oxygen consumption,V02max)。在文献中,术语“功能能力”经常与密切相关但有时不同的术语互换使用,例如“功能锻炼能力”[3]、“工作能力”[4]、“身体素质”[4,5]、“身体机能”[6]、“心肺功能”[6]、“运动耐量”[7]、“运动能力”[8]、“心肺适能”[9,10]、“功能状态”[11,12]、“步行能力”[13]、“有氧力量”[14]、“有氧活动能力”[14]、“行走耐力”[15],以及“心血管健康”[14]等。

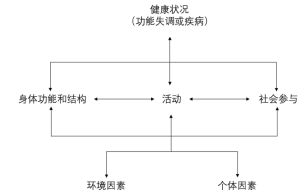

评估患者功能能力的概念源于对健康的生物-心理-社会医学模型的逐步理解,在这个模型中,疾病(或损伤)不仅导致正常身体功能或结构的紊乱,而且限制人的日常活动能力,制约个人参与履行社会责任和义务(图1)[16]。因此,除了治疗和缓解潜在的或原发性的生理功能紊乱之外,对此类人群的最佳照护还需要测量、评估和改善疾病相关的活动限制及参与限制[17]。

功能能力客观量化的金标准测试——CPET,是一个高度复杂的基于实验室的测试,需要特殊的昂贵设备和经过专门培训的人员。因此,尤其是在初级卫生保健中,患者不易获得,亟需要更简单但同样有效可靠的功能能力现场测量[4,17,18]。目前,有关功能能力研究的最广泛的、有效且可靠的现场测量方法是6分钟步行试验(6MWT)——一种更简单、更便宜的测试,它使用六分钟步行距离(six-minute walk distance,6MWD)来量化功能能力。患者以自行选择的速度在坚硬的表面上,例如在医院走廊步行[1,2,19,20]。由于CPET期间测量的 VO2max 是评估健康的生理紊乱区域,而在 6MWT 期间测量的 6MWD 主要评估活动限制区域。因此,6MWT在患者的功能评估中对CPET进行了补充,在无法进行CPET的时候,6MWT可以作为替代方案。尽管存在一些局限性,但 6MWT 的实用性已在许多慢性成人和儿童疾病中得到证实,涵盖心肺、肌肉骨骼、神经肌肉、代谢、内分泌和血液系统[1,22,23]。

尽管关于 6MWT 的各个方面存在大量且不断增加的文献[例如,其测量特性[2,15,22-29]、临床效用和方法论[1,15,19,27,30-33]、以及参考标准[20,34-40]],但很少有一篇论文尝试按照详细时间顺序记录并呈现其演变发展的重要里程碑事件,包括从先前存在的功能能力测量方法到目前最广泛使用的功能能力测量方法。这篇论文将提供6MWT测试“一站式服务”和历史方面的最新参考资料以及关键文献资源,例如,对6MWT测试的各个方面进行的系统评价/Meta分析,以造福临床从业人员和研究人员。

方法与结果

作为之前尼日利亚健康儿童6MWT课题文献检索的一部分,从2013年到2018年8月,我们在多个数据库和搜索引擎(PubMed,Google Scholar,Scopus,SciELO,Google,Yahoo以及Bing)上对与6MWT相关的论文进行了广泛、不受限制的搜索。使用的检索词包括“六分钟步行测试”(“six-minute walk test”)和它的变体,比如“6MWT”、“6分钟步行测试”(“6-minute walk test”)、“6分钟步行测试”(“six-minute walking test”)以及各种形式的“功能能力”(“functional capacity”),例如“运动锻炼能力”(“functional exercise capacity”)、“运动能力”(“exercise capacity”)。为了检索一些6MWT历史层面的特定文献,检索词“历史”(“history”)也包含在其中。

入选论文在发表时间、文献类型(期刊全文、学位论文、会议摘要或海报)、文献地域来源、研究对象年龄范围或发表语言方面没有限制。对于非英文文献,向作者请求英文翻译;当无法获得时,翻译在谷歌翻译的帮助下完成。考虑到这是篇叙述性综述,所以对于文献没有应用严格的质量标准筛选,只要文献信息与预先存在测量功能能力的6MWT的时间顺序发展相关,并将其用作衡量疾病和健康功能能力的主要标准,为临床使用制定参考标准的文献均被纳入。

我们对所选文章的参考文献进行了进一步的检索以获得更多的相关文献。检索到的文献存储在一个数据库中,在需要的时候进行使用。数据库中有一篇最初用阿拉伯语撰写的选定文章[45],作者为我们提供了英文翻译;对于其他三篇用西班牙语书写的文献[46-48],则使用谷歌翻译将其翻译成了英语。

讨论

从实验室到现场测量

20世纪见证了基于实验室的CPET的稳步发展和精密气体测量设备的研制[6,49,50]。随着20世纪20年代早期自行车测力计的发明,最大摄氧量(VO2max)即锻炼者在最大努力CPET期间消耗的最大氧气量,被公认为功能能力测量的金标准[5,6,10,50-52]。Taylor、Mitchell等研究人员发表了早期的执行CPET的标准化方案。然而,有人担心CEPT除了需要复杂的设备外,还相对耗时,因为一次只能测试一个人。因此,基于现场功能能力测量的探索初衷是建立有效和可靠的测试方法,使这些测试可以利用相对简单的设备,同时对大量健康个体(军人)进行评估[4,18,53]。

引用最多、最早记录在案的尝试是Balke在1963年报道的[4]。作者通过量化一组受试者以最快速度在跑步机上跑步时的耗氧量来确定VO2max。此后,试者以尽可能快的速度在田野上跑1英里(1英里≈1609.34米),持续不同的时间,并计算达到的速度。作者观察到,跑步12~20 分钟获得的耗氧量(VO2)与在跑步机上获得的最大耗氧量相似。因此得出的结论是,15分钟跑步试验(15-minute run test,15MRT)与最大努力CPET的结果是相当的。随后,这个测试被应用于航空工作人员、肥胖受试者和患者的评估。

1968年,Cooper[18]试图通过对115名空军人员以最快的速度跑12分钟[12分钟跑步试验(12-minute run test,12MRT)]进行研究,来改进Balke的15MRT。跑步试验计算的氧气消耗与在跑步机上获得的VO2max有极好的相关性(相关系数=0.897),因此,作者认为12MRT与Balker的15MRT有相似的效果。随后Cooper的12MRT被广泛地用于军队人员和运动员的功能评估。Cooper[54]随后发布了基于年龄和性别的列线图,用于根据 12MRT 期间达到的距离估算VO2max。

1976年,McGavin和同事[7]认为步行比在跑步机上跑步或在测力计上骑自行车更能模拟日常活动;因此,在步行测试期间获得的距离可以比骑自行车或跑步更能反映日常功能损害。这个观点与Spiro和同事们[55]早期研究的结果是一致的,他们的研究表明评估功能能力不需要最大程度的用力(如跑步时可能发生的)。因此,McGavin等人[7]将Cooper的12MRT修改为12分钟步行测试(12MWT),并将其应用在患有慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)的受试者中,让他们在医院室内的走廊里行走。受试者在12分钟内步行距离(12MWD)与CPET期间达到的VO2max显著相关。

同样,在1977年,Mungall和Hainsworth[9]证明了12MWT作为功能能力测量方法的可重复性。这些研究人员还观察到,相比于第1秒用力呼气容积(forced expiratory volume in one second,FEV1),12MWD是一种更好、更客观的功能能力衡量标准。此后,McGavin 的 12MWT 作为客观衡量功能能力的标准得到普遍应用,包括在成人慢性肺病的临床试验中[56-62]。

成人受试者中的 6MWT

McGavin的12MWT一直作为常用的功能能力现场测量方法,直到1982年,Butland和同事们[63]认为12MWT“对研究人员来说很费时,又让患者筋疲力尽”。因此,该小组验证了以下假设,即持续时间较短的步行测试[两分钟步行测试(two-minute walk test,2MWT)和6MWT]在功能能力测量方面与12MWT具有相似的效能。据观察,受试者在前两分钟内达到最快步行速度,在随后的两分钟间期内获得了稳定的距离。这3个测试之间的相关性非常好(6MWD vs 12MWD,相关系数=0.955;2MWD vs 12MWD,相关系数=0.864;6MWD vs 2MWD,相关系数=0.892;受试者人数=30),平均12MWD是平均6MWD的2倍,平均6MWD大约是平均2MWD的3倍。作者因此得出结论,6MWT是在相对较长的12MWT和相对较差的2MWT之间的“明智妥协”。

在Butland的6MWT“诞生”两年后,Guyatt等人[8]报道称,相比于2MWT,6MWT能更好地检测出具有临床意义改变的功能能力。此后,6MWT逐渐成为在成人慢性疾病中最常使用的功能能力现场测量方法[23]。它主要用于成人慢性气道疾病中,直到1985年Guyatt等人[11,64,65]报道6MWT与CPET和纽约心脏学会(New York Heart Association,NYHA)成人慢性心力衰竭的功能分类评分显著相关。同样,在1986年,Lipkin等人[66]发现6MWT在测量成人慢性心衰患者的功能能力方面,比CPET有用且不费力。随后,6MWT的用途从心肺领域扩展到代谢疾病、血液疾病、神经肌肉疾病、风湿病、精神疾病、肾脏疾病以及慢性感染性疾病[1,20,23,24,30,67-69]。

儿童受试者中的 6MWT

最早在儿童受试者中应用6MWT的报道见于1996年的两项独立研究,分别是Gulmans等人[70]进行的荷兰儿童研究以及Nixon等人[71]进行的美国儿童研究。作者证明了6MWT在衡量囊性纤维化和终末期心肺疾病儿童功能能力方面的有效性和可靠性。随后,6MWT 被测试并用于其他儿童慢性疾病,例如先天性心脏病、终末期肾病、肥胖症、脑瘫和HIV感染[22,72-74]。

6MWT的标准化

1984年,Guyatt等人[8]在一项囊括43例成人慢性肺心病患者的随机干预性研究中发现:在6MWT期间采用不同的激励方式会显著影响最终达到的步行距离,因此建议对6MWT进行标准化。然而,直到2002,年美国胸腔学会(American Thoracic Society,ATS)临床肺功能实验室能力标准委员会才发布了第一个标准指南,以协调其临床应用并加强不同研究之间的国际比较,直至这时,6MWT的全面标准化才得以实现。该声明提供了关于患者选择、设备、适应证和禁忌证、标准化每分钟的激励方式和成人人群测试的其他方面。

在随后两次姗姗来迟的对2002年 ATS 指南进行的审查中,ATS联合欧洲呼吸学会(European Respiratory Society,ERS)提供了关于6MWT的测量特性[2]和“标准操作流程”[30]的更新。与2002年的指南相比,这些更新更强调在干预后评估时需要重复测试以解释“学习效果”。2015年,波兰呼吸学会发布了关于6MWT的共识指南[19]。

成人6MWT参考标准

随着6MWT作为功能能力测量方式的有效性和可靠性的确立,为了指导测试的临床解释,建立参考标准(带或不带预测回归方程的参考值)的需求变得明显。Enright Sherill于1988年通过对美国290名健康成年人进行研究,发表了第一个成人参考标准和方程式。身高、体重、体重指数(BMI)、年龄和性别是6MWT的独立预测因素。此后,Troosters等人[76]以及Gibbons等人[77]分别于1999年和2001年发表了在比利时健康人群和加拿大健康人群中获得的参考方程式。

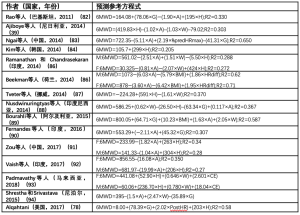

这三项研究发表于2002年ATS指南发表之前,其特点是测试方案间的差异很大,包括路线长度和激励方式。在2002年ATS指南发表之后,世界各民族、各地理区域的参考标准和方程式得到了广泛的发展[20,39,78-81]。Salbach等人[80]于2014年发表了对20项研究进行的系统评价,这些研究涵盖了来源于美国、欧洲、亚洲和非洲成年人群的预测参考方程。表1显示了在 Salbach 的系统综述之后发表的其他方程式。

Full table

6MWT在儿科年龄组中的参考标准

儿童 6MWT 参考标准的发布落后于成年人,可能是由于对安全性和有效性的担忧。此外,由于缺乏关于 6MWT 的儿童群体特定指南(迄今为止),对健康和患病儿童受试者的研究将现有的成人指南外推到儿童,并经常进行方法上的修改,例如使用更短的路线长度、激励方法,或设置“安全追逐者”等[22,34-36,38,95-98]。

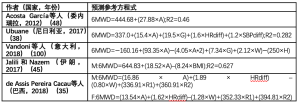

2001,Escobar等人[47]对智利人群进行了研究,发表了首个来源于健康儿童的参考标准(没有方程式的平均6MWT)。后来在2007年,Li等人[99]发表了第一个中国健康儿童青少年6MWD的预测回归方程。随后,来源于欧洲、北美洲的美国、亚洲和非洲健康儿童的参考标准(带或不带方程式)发布。这些参考标准和方程式大多数都已经被总结在Cacau[36]、Mylius[34]和Rodríguez-Núñez等人[40]的3篇独立的系统评价中。没有包括在这些综述中或者发表于这些综述之后的参考方程式请见表2[34,36,38]。

Full table

在成人和儿童人群研究中,通过观察到参考值的广泛变化,已经了解/证明了每个民族、地理区域特定的参考值和方程的需求[34,36,40,79,80]。因此,独立于测试方法的差异以及其他影响变量(如人体测量学特征、种族和民族),显著影响受试者在6MWT上的表现[34,36,40,101]。

新方法和创新

过去10年出现了旨在提高6MWT的管理效率以及减少测试所需的人力方面的有趣的创新。例如,Du和同事们[27,102]将6MWT的使用概念化为一种以家庭为基础的“自我管理”式的测量社区慢性心力衰竭患者的功能能力(家庭心脏步行测试)。这样可为门诊慢性心脏病患者提供一种自我监测工具(类似于糖尿病护理中的自我监测血糖仪或慢性肺部疾病中的手持式肺活量计),有助于在家时早期发现并追踪功能能力的变化[27]。

随着智能手机的出现以及广泛使用,6MWT的管理也随着智能手机应用程序的开发和验证得到了进一步加强,这些应用程序将计圈器、秒表和计算器的功能结合到一个单一的应用程序中,以用于在家庭或诊所环境下进行6MWT[103]。此外,目前已开发的应用程序不仅可以执行上述操作,还可以使用手机上的传感器(如陀螺仪)自动推导6MWD(不计算圈数),并且将数据远距离传输给临床医生[104]。因此,6MWT已经成为衡量慢性疾病患者功能能力的相关指标。

结论

从20世纪80年代初首次被记录使用以来,6MWT已成为成人和儿童人群中最常用的、有效的、可靠的基于现场的功能能力客观测量方法[23]。关于其发展、效用、测量特性以及各民族、各地理人群的参考方程的数据非常丰富,且正在不断增长。除了按照时间顺序记录其多年来的演变,这篇综述还重点介绍了对其发展做出贡献的杰出人物或团体。然而,仍需要制定针对儿童和青少年的特定指南。此外,北美和其他撒哈拉以南非洲地区等种族的儿童也需要参考方程。

Acknowledgements

We express gratitude to authors who provided translations or full texts of their works on request.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jxym.2018.11.01). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- ATS Committee on Proficiency Standards for Clinical Pulmonary Function Laboratories. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111-7. Erratum in: Erratum: ATS Statement: Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test [Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh SJ, Puhan MA, Andrianopoulos V, et al. An official systematic review of the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society: measurement properties of field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1447-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association. Functional exercise capacity and objective assessment. 9th edition. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co., 1964.

- Balke B. A simple field test for the assessment of physical fitness. REP 63-6. Rep Civ Aeromed Res Inst US 1963:1-8.

- Robinson S. Experimental studies of physical fitness in relation to age. Arbeitsphysiologie 1938;10:251-323.

- Taylor HL, Buskirk E, Henschel A. Maximal Oxygen Intake as an Objective Measure of Cardio-Respiratory Performance. J Appl Physiol 1955;8:73-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGavin CR, Gupta S, McHardy G. Twelve-minute walking chronic bronchitis for assessing disability. Br Med J 1976;1:822-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guyatt GH, Pugsley S, Sullivan MJ, et al. Effect of encouragement on walking test performance. Thorax 1984;39:818-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mungall IP, Hainsworth R. Assessment of respiratory function in patients with chronic obstructive airways disease. Thorax 1979;34:254-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shephard RJ, Allen C, Benade AJ, et al. The maximum oxygen intake. An international reference standard of cardiorespiratory fitness. Bull World Health Organ 1968;38:757-64. [PubMed]

- Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, et al. The 6-minute walk: A new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J 1985;132:919-23. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health 2001;18:237. Available online: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. Assessed 2015-08-23.

- Takeuchi Y, Katsuno M, Banno H, et al. Walking capacity evaluated by the 6-minute walk test in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve 2008;38:964-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takken T, Bongers BC, Van Brussel M, et al. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Pediatrics. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:S123-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steffen TM, Nelson RE. Measurement of Ambulatory Endurance in Adults. Top Geriatr Rehabil 2012;28:39-50. [Crossref]

- World Health Organization. Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health 2002;1149:1-22. Available online: http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf

- Bui KL, Nyberg A, Maltais F, et al. Functional Tests in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Part 1: Clinical Relevance and Links to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:778-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper KH. A Means of Assessing Maximal Oxygen Intake. JAMA 1968;203:201-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Przybyłowski T, Tomalak W, Siergiejko Z, et al. Polish Respiratory Society guidelines for the methodology and interpretation of the 6 minute walk test (6MWT). Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2015;83:283-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andrianopoulos V, Holland AE, Singh SJ, et al. Six-minute walk distance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Which reference equations should we use? Chron Respir Dis 2015;12:111-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rostagno C, Gensini GF. Six minute walk test: a simple and useful test to evaluate functional capacity in patients with heart failure. Intern Emerg Med 2008;3:205-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bartels B, de Groot JF, Terwee CB. The six-minute walk test in chronic pediatric conditions: a systematic review of measurement properties. Phys Ther 2013;93:529-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solway S, Brooks D, Lacasse Y, et al. A qualitative systematic overview of the measurement properties of functional walk tests used in the cardiorespiratory domain. Chest 2001;119:256-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vickers RR. Walk tests as indicators of aerobic capacity. California: Naval Health Research Center, 2002.

- Bui KL, Nyberg A, Maltais F, et al. Functional Tests in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Part 2: Measurement Properties. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:785-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shoemaker MJ, Curtis AB, Vangsnes E, et al. Triangulating Clinically Meaningful Change in the Six-minute Walk Test in Individuals with Chronic Heart Failure: A Systematic Review. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J 2012;23:5-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Du H, Newton PJ, Salamonson Y, et al. A review of the six-minute walk test: Its implication as a self-administered assessment tool. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2009;8:2-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bellet RN, Adams L, Morris NR. The 6-minute walk test in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: validity, reliability and responsiveness-a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2012;98:277-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schrover R, Evans K, Giugliani R, et al. Minimal clinically important difference for the 6-min walk test: literature review and application to Morquio A syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017;12:78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holland AE, Spruit MA, Troosters T, et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1428-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Enright PL. The Six-Minute Walk Test. Respir Care 2003;48:783-5. [PubMed]

- Faggiano P, D’Aloia A, Gualeni A, et al. The 6 minute walking test in chronic heart failure: indications, interpretation and limitations from a review of the literature. Eur J Heart Fail 2004;6:687-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dunn A, Marsden DL, Nugent E, et al. Protocol variations and six-minute walk test performance in stroke survivors: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Stroke Res Treat 2015;2015:484813. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mylius CF, Paap D, Takken T. Reference value for the 6-minute walk test in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Expert Rev Respir Med 2016;10:1335-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Assis Pereira Cacau L, Carvalho VO, Dos Santos Pin A, et al. Reference Values for the 6-min Walk Distance in Healthy Children Age 7 to 12 Years in Brazil: Main Results of the TC6minBrasil Multi-Center Study. Respir Care 2018;63:339-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cacau LA, de Santana-Filho VJ, Maynard LG, et al. Reference Values for the Six-Minute Walk Test in Healthy Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2016;31:381-8. [PubMed]

- Bohannon RW. Six-Minute Walk Test: A Meta-Analysis of Data From Apparently Healthy Elders. Top Geriatr Rehabil 2007;23:155-60. [Crossref]

- Ubuane PO. Predictive reference equation for the six-minute walk distance of apparently healthy primary school pupils in Ikeja, Lagos State. Faculty of Paediatrics, West African College of Physicians, 2017.

- Ajiboye OA, Anigbogu CN, Ajuluchukwu JN, et al. Prediction equations for 6-minute walk distance in apparently healthy Nigerians. Hong Kong Physiother J 2014;32:65-72. [Crossref]

- Rodríguez-Núñez I, Mondaca F, Casas B, et al. Normal values of 6-minute walk test in healthy children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Chil Pediatr 2018;89:128-36. [PubMed]

- Vuckovic KM, Fink AM. The 6-Min Walk Test: Is It an Effective Method for Evaluating Heart Failure Therapies? Biol Res Nurs 2012;14:147-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grinnell D. The Historical and Clinical Significance of the 6- Minute Walk Test 1960. Available online: http://www.slideshare.net/dgrinnell/the-historical-and-clinical-significance-of-the-6-minute-walk-test?from_action=save (accessed July 31, 2015).

- Zieliński J. Six minute walking test: an old tool with new applications. Multidiscip Respir Med 2010;5:241-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh N, Thanikachalam S, Satyanarayana M, et al. Six minute walk test: a literary review. Sri Ramachandra J Med 2011;4:30-4.

- Jalili M, Nazem F. Design and Cross-Validation of Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) Prediction Equation in Iranian healthy Males Aged 7 to 16 Years. J Ergon 2017;5:17-25. [Crossref]

- Gatica D, Puppo H, Villarroel G, et al. Reference values for the 6-minutes walking test in healthy Chilean children (article in Spanish). Rev Med Chile 2012;140:1014-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Escobar M, López A, Veliz C, et al. Six minute walking test in healthy Chilean children (article in Spanish). Kinesiologia 2001;62:16-20.

- Acosta García EJ, Rodriguez LS, Barón MA, et al. Six-minute walk test in school children (article in Spanish). Salus 2012;16:25-9.

- Astrand PO, Saltin B. Maximal oxygen uptake and heart rate in various types of muscular activity. J Appl Physiol 1961;16:977-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seiler S. A Brief History of Endurance Testing in Athletes. Sportscience 2011;15:40-6.

- Mitchell JH, Sproule BJ, Chapman CB. The physiological meaning of the maximal oxygen intake test. J Clin Invest 1958;37:538-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hill AV. Muscular activity. Oxford, England: Bailliere, 1926.

- Mackenzie B. Cooper Test - 12 minute run to assess your VO2max. Www 1997. Available online: http://www.brianmac.co.uk/gentest.htm (accessed August 12, 2015).

- Cooper KH. The new aerobics. Bantam Books, 1970.

- Spiro SG, Hahn HL, Edwards RH, et al. An analysis of the physiological strain of submaximal exercise in patients with chronic obstructive bronchitis. Thorax 1975;30:415-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGavin CR, Artvinli M, Nace H, et al. Dyspnoea, disability and distance walked: Comparison of estimates of exercise performance in respiratory disease. Int J Rehabil Res 1980;3:235-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cockcroft AE, Saunders MJ, Berry G. Randomised controlled trial of rehabilitation in chronic respiratory disability. Thorax 1981;36:200-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calverley PM, Leggett RJ, Flenley DC. Carbon monoxide and exercise tolerance in chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981;283:878-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butland RJ, Pang JA, Geddes DM. Carbimazole and exercise tolerance in chronic airflow obstruction. Thorax 1982;37:64-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leitch AG, Morgan A, Ellis DA, et al. Effect of oral salbutamol and slow-release aminophylline on exercise tolerance in chronic bronchitis. Thorax 1981;36:787-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly JF, Shaylor JM, Fromings KM, et al. The use of the 12 minute walking test in assessing the effect of oral steroid therapy in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Br J Dis Chest 1982;76:374-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams AJ, Osman J, Skinner C. Effects of naftidrofuryl on breathlessness and exercise tolerance in chronic bronchitis. Thorax 1982;37:617-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butland RJA, Pang J, Gross ER, et al. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982;284:1607-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guyatt GH, Thompson PJ, Berman LB, et al. How should we measure function in patients with chronic heart and lung disease? J Chronic Dis 1985;38:517-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guyatt GH, Townsend M, Keller J, et al. Measuring functional status in chronic lung disease: conclusions from a randomized control trial. Respir Med 1989;83:293-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lipkin DP, Scriven A J, Crake T, et al. Six minute walking test for assessing exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:653-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adedoyin RA, Erhabor GE, Ojo OD, et al. Assessment of Cardiovascular Fitness of Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis Using Six Minute Walk Test. TAF Prev Med Bull 2010;9:99-106.

- Mbada CE, Onayemi O, Ogunmoyole Y, et al. Health-related quality of life and physical functioning in people living with HIV/AIDS: a case-control design. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ajiboye OA, Anigbogu CN, Ajuluchukwu JN, et al. Exercise training improves functional walking capacity and activity level of Nigerians with chronic biventricular heart failure. Hong Kong Physiother J 2015;33:42-9. [Crossref]

- Gulmans VA, van Veldhoven NH, de Meer K, et al. The six-minute walking test in children with cystic fibrosis: reliability and validity. Pediatr Pulmonol 1996;22:85-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nixon PA, Joswiak ML, Fricker FJ. A six-minute walk test for assessing exercise tolerance in severely ill children. J Pediatr 1996;129:362-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sims Sanyahumbi AE, Hosseinipour MC, Guffey D, et al. HIV-infected Children in Malawi Have Decreased Performance on the 6-minute Walk Test With Preserved Cardiac Mechanics Regardless of Antiretroviral Treatment Status. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2017;36:659-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Groot JF, Takken T. The six-minute walk test in paediatric populations. J Physiother 2011;57:128. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zuk M, Migdal A, Jagiellowicz-Kowalska D, et al. Six-Minute Walk Test in Evaluation of Children with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Pediatr Cardiol 2017;38:754-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Enright PL, Sherrill DL. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:1384-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Troosters T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Six minute walking distance in healthy elderly subjects. Eur Respir J 1999;14:270-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibbons WJ, Fruchter N, Sloan S, et al. Reference values for a multiple repetition 6-minute walk test in healthy adults older than 20 years. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2001;21:87-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani M. Developing a prediction equation for the six-minute walk test in healthy African-American adults. Georgia State University, 2017.

- Casanova C, Celli BR, Barria P, et al. The 6-min walk distance in healthy subjects: reference standards from seven countries. Eur Respir J 2011;37:150-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salbach NM, Brien KKO, Brooks D, et al. Reference values for standardized tests of walking speed and distance : A systematic review. Gait Posture 2015;41:341-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mbada CE, Jaiyeola OA, Johnson OE, et al. Reference Values for Six Minute Walk Distance in Apparently Healthy Young Nigerian Adults (Age 18-35 Years). Int J Sport Sci 2015;5:19-26.

- Rao NA, Irfan M, Haque AS, et al. Six-Minute Walk Test Performance in Healthy adult Pakistani volunteers. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2013;23:720-5. [PubMed]

- Ngai SP, Jones AY, Jenkins SC. Regression equations to predict 6-minute walk distance in Chinese adults aged 55-85 years. Hong Kong Physiother J 2014;32:58-64. [Crossref]

- Kim AL, Kwon JC, Park I, et al. Reference equations for the six-minute walk distance in healthy Korean adults, aged 22-59 years. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2014;76:269-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palaniappan Ramanathan R, Chandrasekaran B. Reference equations for 6-min walk test in healthy Indian subjects (25-80 years). Lung India 2014;31:35-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beekman E, Mesters I, Gosselink R, et al. The first reference equations for the 6-minute walk distance over a 10 m course. Thorax 2014;69:867-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tveter AT, Dagfinrud H, Moseng T, et al. Health-related physical fitness measures: Reference values and reference equations for use in clinical practice. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:1366-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nusdwinuringtyas N. Reference equation for prediction of a total distance during six-minute walk test using Indonesian anthropometrics. Acta Med Indones 2014;46:90-6. [PubMed]

- Bourahli MK, Bougrida M, Martani M, et al. 6-Min walk-test data in healthy North-African subjects aged 16–40 years. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc 2016;65:349-60. [Crossref]

- Fernandes L, Mesquita AM, Vadala R, et al. Reference Equation for Six Minute Walk Test in Healthy Western India Population. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:CC01-4. [PubMed]

- Zou H, Zhu X, Zhang J, et al. Reference equations for the six-minute walk distance in the healthy Chinese population aged 18–59 years. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184669. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaish H, Gupta S, Sharma S. Six Minute Walk Distance and Six Minute Walk Work in Young Adults Aged 18-25. Int J Pharm Med Res 2017;5:464-8.

- Padmavathy KM, Sankaran RS, Oncho TJ, et al. Six-Minute Walk Test: reference values for healthy young adults in Malaysia. Natl J Integr Res Med 2018;9:66-70.

- Shrestha SK, Srivastava B. Six minute walk distance and reference equations in normal healthy subjects of Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J 2015;13:97-101. (KUMJ). [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geiger R, Strasak A, Treml B, et al. Six-minute walk test in children and adolescents. J Pediatr 2007;150:395-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goemans N, Klingels K, van den Hauwe M, et al. Six-minute walk test: reference values and prediction equation in healthy boys aged 5 to 12 years. PLoS One 2013;8:e84120. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDonald CM, Henricson EK, Han JJ, et al. The 6-minute walk test as a new outcome measure in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:500-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morales Mestre N, Audag N, Caty G, et al. Learning and Encouragement Effects on Six-Minute Walking Test in Children. J Pediatr 2018;198:98-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li AM, Yin J, Au JT, et al. Standard reference for the six-minute-walk test in healthy children aged 7 to 16 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:174-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vandoni M, Correale L, Puci MV, et al. Six minute walk distance and reference values in healthy Italian children: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0205792. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dourado VZ. Reference Equations for the 6-Minute Walk Test in Healthy Individuals. Arq Bras Cardiol 2011;96:128-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Du H, Davidson PM, Everett B, et al. Assessment of a Self-administered Adapted 6-Minute Walk Test. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2010;30:116-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brooks GC, Vittinghoff E, Iyer S, et al. Accuracy and usability of a self-administered 6-Minute Walk Test smartphone application. Circ Heart Fail 2015;8:905-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Capela NA, Lemaire ED, Baddour N. Novel algorithm for a smartphone-based 6-minute walk test application: algorithm, application development, and evaluation. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2015;12:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

李赛男

中国医科大学研究生,专业是心血管内科,师从北部战区总医院的王祖禄老师,主要的研究方向是心律失常。(更新时间:2021/8/19)

贺继强

硕士及博士均就读于中南大学湘雅医院手显微外科。博士就读期间,在国家留学基金委的资助下赴美国约翰霍普金斯大学整形外科学习2年4个月。约翰霍普金斯大学整形外科是世界知名的同种异体手移植中心,我所在的同种异体复合组织移植实验室聚焦于显微外科培训,复合组织移植的基础与临床,器官与组织的低温保存和机器灌注。在美国学习期间整理湘雅医院手显微外科的解剖学和临床病例资料,发表sci论文数篇。(更新时间:2021/8/19)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Ubuane PO, Animasahun BA, Ajiboye OA, Kayode-Awe MO, Ajayi OA, Njokanma FO. The historical evolution of the six-minute walk test as a measure of functional exercise capacity: a narrative review. J Xiangya Med 2018;3:40.