局部晚期非小细胞肺癌的诊断和分期

引言

根据国际肺癌研究协会(International Association on the Study of Lung Cancer,IASLC)最近更新的非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)分期,T4分期包含截然不同的实体:>7 cm的肿瘤;在同侧肺的另一个肺叶中有卫星肿瘤结节的肿瘤,累及椎体、大血管、心脏、纵隔、气管、食管、喉返神经和膈肌的肿瘤(在最新版本的TNM中从T3开始分期上调)[1]。尽管由于数据量相对较少,不可能对不同的T4亚类进行详细的生存亚组分析,但观察到在同一肺的不同肺叶中有第二个结节的患者预后略差。

Farjah 等[2]调查过去几十年中T4期NSCLC治疗的趋势,发现从监测、流行病学和最终结果项目(SEER)数据库中筛选的13 000例患者中,只有9%经高度选择的患者接受了手术。此外,关于T4切除的结局证据较差,通常是对单机构经验的回顾性分析[3];然而,T4患者的长期结局通常不佳,主要取决于N状态。因此,T4肿瘤的术前分期起着关键作用,应慎重仔细地进行。因此,T4期NSCLC分期可能需要根据解剖和病理情况进行几个步骤;此外,适当的术前检查对生存期有直接影响[4]。初步评估依赖于对患者准确的临床评价、详细病史(包括可能的风险因素),使用造影剂的计算机断层扫描(CT)和2-18F-2-脱氧葡萄糖(FDG-PET)-CT[5]。

最近,磁共振成像(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI)和PET-MRI被提出在肺癌的诊断中起作用,但其与CT相比的益处仍未在前瞻性研究中得到证实[6],目前将其常规使用留给选定的患者。

功能评估

T4期NSCLC可能需要扩大手术,不仅需要切除周围结构,还需要切除大部分肺实质直至完成肺切除术。因此,在任何计划治疗前,详细评价肺和心脏功能至关重要。必须考虑预期寿命、肿瘤分期、体能状态和合并症等因素。

胸外科手术后心血管并发症的发生风险为2%~3%[7],因此需要进行心脏病学术前评价。并非所有患者均应接受侵入性心脏病学检查,只有那些并发症风险较高的患者应该接受,这些患者可以根据合并症的存在或病史进行选择和分层[8,9]。

应使用肺功能检查(pulmonary function tests,PFTs)和一氧化碳弥散量(diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide,DLCO)评价肺功能。第一秒用力呼气容积(forced expiratory volume in the first second,FEV1)和DLCO显示与发病率和死亡率严格相关,尤其是术前FEV1<30%和>60%与呼吸系统疾病相关,且呼吸系统疾病发生率分别为43%和12%[10],而术前DLCO<60%与40%的肺部发病率高达25%的术后死亡率相关[11]。有趣的是,高达40%的术前FEV1>80%的患者DLCO<80%,其中7%患者术后DLCO<40%;因此,无论FEV1值如何,均应研究DLCO[12,13]。与术前值结合,可以计算预测术后(PPO)FEV1和DLCO,它们是非常的预后因素[9,14]。

在该患者队列中,通常在术前进行诱导治疗。一些作者报告了诱导治疗对肺功能的不利影响;尤其DLCO似乎是受影响最大的参数[15],即使长期影响尚不明确[16]。因此,新辅助治疗后应重复进行PFT和DLCO检查。

接受全肺切除术的患者肺功能通常受损更严重,功能储备也降低[17,18];因此,对于此类患者,必须更仔细地评价肺和心脏功能[19]。Brunelli及其同事[18]建议在肺切除术前常规进行心肺运动试验(cardiopulmonary exercise test,CPET),无论术前、术后PFT和DLCO数据如何。同时,在肺切除术的围手术期管理中,必要时应进行超声心动图检查,以评估右心室功能引起或加重肺动脉高压的风险[20]。

T类诊断

诊断试验的目的应是最大限度地提高诊断和分期的准确率,避免不必要的侵入性检测[21]。在大的中心型NSCLC中,尤其是既往咯血发作的患者,痰细胞学检查可能是第一步诊断,灵敏度和特异性分别为42%~97%和68%~100%。然而,该结果受到癌症位置和采集标本数量的强烈影响[22];因此,可以进行痰细胞学检查,但阴性结果需要进一步研究[21]。对于位于中央的肿块,支气管镜检查是获得组织学或细胞学检查标本的首选方法;总体灵敏度为88%[21],但据报告,钳取活检、清洗和刷检的总体灵敏度分别为74%、48%和59%。此外,支气管内针吸可提高支气管镜检查的灵敏度[23]。但在外周病变的情况下,数据不太可喜,总体度为78%,在这种情况下,经支气管针吸活检似乎是最的工具(度为65%)[22]。尽管如此,使用X线透视[24]、更多标本[25]和更大的肿瘤直径(尤其是>2 cm时)可能会提高灵敏度[26,27]。径向支气管内超声(r-EBUS)和电磁导航(electromagnetic navigation,EMN)是相对较新的技术,可提高外周结节内镜手术的灵敏度。在Meta分析中,r-EBUS显示外周结节的灵敏度为73%,特异性为100%,对2 cm以上病变的诊断率更高[28];此外,一项单中心前瞻性研究显示,r-EBUS对外周结节的诊断率为74%[29]。同时,EBUS和EMN的联合使用可能导致93%的诊断率[30]。尽管如此,经胸廓针吸(transthoracic needle aspiration,TTNA)目前被认为是诊断外周NSCLC的金标准,灵敏度为90%[21];CT引导的TTNA在灵敏度方面似乎比X线透视更好(92% vs 88%)[22]。此外,与细针穿刺(fine needle aspiration,FNA)相比,使用针芯活检似乎具有一些优势;事实上,尽管对恶性肿瘤的灵敏度相似,但其在定义非恶性病变方面可达到更好的结果,并可产生足够的组织用于遗传和突变分析。重要的是,TTNA具有相对较高的假阴性结果率[31]和中度并发症发生率[32]。

上腔静脉(SVC)受累

肺癌侵犯上腔静脉(superior vena cava,SVC)相当少见,占不到1%的可手术患者。这些肿瘤通常位于中央,可能需要全肺切除,并可能浸润膈神经,因此在大多数情况下必须牺牲膈神经。

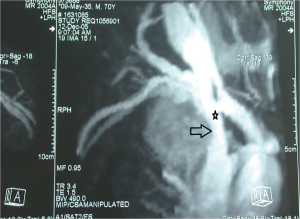

在涉及侵犯上腔静脉的NSCLC的术前管理中,可以通过从双上肢注射造影剂的腔静脉造影术研究浸润的范围,即使该技术可能因覆盖结构的存在而存在严重偏倚,这可能导致图像不确定[33,34]。最近,CT血管造影(CTA)和磁共振血管造影(MRA)被用于评估血管受累(图1)。与腔静脉造影相比,CTA和MRA在区分不同解剖结构和最终血管浸润程度方面显示出更高的灵敏度[33];有趣的是,一些作者报告非增强和增强MRA的相似灵敏度,这可能进一步降低检测的侵入性[35,36]。此外,Ohno及其同事[37]报告,使用心电图(electrocardiographically,ECG)触发MRA的放射图像质量更好。最后,必须进行超声心动图检查,以排除右心房血栓的存在[34]。

气管和隆突受累

支气管镜检查是气道受累检查的基础。Mitchell及其同事[38]建议术前使用硬性支气管镜,其不仅可以验证切除的可行性,还可以进行详细的手术计划。此外,术前硬性支气管镜检查可用于进行内镜减瘤术,以预防术后肺炎的发生。

主动脉受累

在一项大型欧洲多中心研究[39]和一篇关于NSCLC侵犯胸主动脉的单中心论文[40]中,作者建议应通过对比CT和MRI,研究可能的主动脉浸润,这可以充分确定血管浸润的特殊性。另一方面,没有作者建议常规使用血管造影检查。

左心房受累

非小细胞肺癌心包内侵犯心脏通常被认为是手术的禁忌证;然而,左心房可能受累于肿瘤的直接扩散或来自肺静脉的肿瘤性血栓。超声心动图是评估心脏受累的一级检测手段;特别是经食管超声心动图可用于术前检查,也可用作术中监测,以验证左心房钳夹对血液动力学的影响,如Stella同事在31个连续病例系列中所描述的那样[41]。除超声心动图外,Galvaing等人[42]建议常规使用术前心脏MRI来评估可能的房间隔浸润。在心脏受累的情况下,应使用心肺旁路(cardio-pulmonary bypass,CPB),即使许多作者报告使用了钳夹缝合技术。

肺上沟肿瘤

根据肿瘤向脊椎、锁骨下血管或胸壁旁臂丛的延伸情况,可考虑将上沟肿瘤划分为T3或T4。尽管T4并不被认为是可手术的,但Waseda及其同事[43]报告在有经验的医生手中,T4具有与T3相似的长期结果。术前分期应始终考虑MRI,以更好地确定周围结构的受累情况及手术入路。

N类诊断

N状态被认为是T4肿瘤治疗中最重要的预后因素。事实上,除了对T成分手术可切除性的技术评估外,淋巴结受累情况对于决定更好的治疗路径至关重要。在一项多中心研究中,Reed等[44]证实了PET扫描的实用性,尤其是用于纵隔淋巴结和非预期转移的分期,而Cerfolio等[45]建议,如果纵隔淋巴结站或远处器官的PET扫描结果为阳性,应行进一步分析和可能的组织学活检以确认阳性。美国国家综合癌症网络(National Comprehensive Cancer Network,NCCN)和欧洲胸外科医师学会(European Society of Thoracic Surgeons,ESTS)[46]指南也强烈建议常规使用PET扫描,与其他放射学技术相比,其灵敏度(80%~90%)和特异性(85%~95%)更高。同时,最近的一项Meta分析[47]比较了PET-CT和弥散加权MRI,发现后者的灵敏度更好;然而,迄今为止,没有高级别证据证明常规使用磁共振进行N成分的特异性诊断是合理的。除此之外,ESTS指南[46]指出,单独使用PET-CT对纵隔淋巴结进行分期存在一些例外情况,即肿瘤>3 cm,疑似N1,CT或PET扫描未发现疑似淋巴结的中心位置肿瘤。因此,很明显,对于T4肿瘤,应始终谨慎对待PET-CT在纵隔淋巴结检查中的阴性预测值(negative predictive value,NPV),并且,在术前放射学检查完全阴性的情况下,也应进行进一步分析。

EBUS技术和内窥镜超声(endoscopic ultrasounds,EUS)是内窥镜医生和胸外科医生常用的技术,它们允许探查几乎所有的纵隔淋巴结站[48],除了不建议使用这些技术进行探查第5站和第6站。试验和Meta分析[49-54]研究了每种技术的特异性和灵敏度,发现联合使用EUS和EBUS的结果最佳(肺癌纵隔分期的灵敏度为83%~94%),减少了进一步侵入性诊断程序的需要[46,55,56]。淋巴结分期的外科方法包括视频辅助纵隔镜检查(video-assisted mediastinoscopy,VAM)、视频辅助纵隔镜淋巴结切除术(VAMLA)[57]、经颈扩展纵隔淋巴结切除术(TEMLA)[58]和VATS;虽然这些手术是标准化和安全的手术,但与内窥镜手术相比,它们的发病率更高。VAM是用于评估病理性纵隔淋巴结的最广泛的外科手术;它允许对所有气管旁站、隆突下站和最近的肺门站进行组织学采样;相反,第5、6、8、9站是无法到达的[46]。一些机构报道过VAMLA和TEMLA的使用,但它们的使用既不是很广泛的,也不是ESTS指南所建议的,因为发病率和死亡率明显高于VAM。另一方面,对第5站和第6站的调查可能需要不同的方法。VAMLA和TEMLA的NPV最高,达到了令人印象深刻的98.7%[46]。此外,VATS和前纵隔切开术(Chamberlain手术)也可作为诊断程序。

有趣的是,Mitchell和他的同事们提倡在手术切除侵入气管的肿瘤之前,使用纵隔镜检查,它不仅可以在复杂的外科手术之前分析结节状态,而且还可以通过创建气管前间隙来释放气管[38]。

通常需要对局部晚期NSCLC进行诱导治疗。因此,在新辅助治疗后必须进行再分期,以重新评估淋巴结状态,从而给出适当的指示[59]。CT扫描和PET-CT在诱导治疗后的再分期中失去了部分灵敏度、特异性和NPV,因此不完全可靠,将导致分期过高或过低[60]。事实上,EBUS和EUS应作为评估疾病可能持续存在的一线手术,但其灵敏度和假阴性率表明,在结果为阴性的情况下应使用手术分期[59,61,62]。纵隔镜检查在初治患者中是可行和安全的,即使在诱导治疗后也是如此[63],但补救纵隔镜检查是一种可行但具有挑战性的手术,应在有经验的中心谨慎进行[59,61]。

M类诊断

存在远处转移是T4期NSCLC手术切除的禁忌证,应在任何侵入性操作之前对其进行检查。在研究18FDG PET-CT检测肺癌转移准确性的Meta分析中,Li及其同事[64]报告灵敏度和特异性分别为92%和97%。同时,比较PET-CT和MRI的两项Meta分析[65,66]发现灵敏度和特异性结果相似,表明联合使用可能改善术前分期。然而,由于基线脑活动,PET-CT不适用于对大脑进行正确的分期。对于Ⅲ期或Ⅳ期肿瘤,美国胸科医师学会(American College of Chest Physicians,ACCP)指南建议使用MRI或CT扫描患者脑部,即使在无脑部受累临床体征的患者中也是如此[5]。同时,一项韩国单机构研究表明,仅建议在风险因素较高的患者中进行脑部评估[67]。

总结

T4肿瘤代表了NSCLC的罕见表现,对于胸外科医生来说,它们可以被认为是双重挑战:它们意味着正确的分期和对手术切除术可行性的正确评价。事实上,N状态和干预手段的根治性都是两个基本的预后因素,强烈影响长期结果。为了选择正确的治疗方法,多学科讨论是强制性的,多学科团队应包括胸外科医生、肿瘤学家、放射肿瘤学家和介入肺科医生。此外,在T4期NSCLC的治疗中应始终遵循三个要点:首先,T4肿瘤的手术治疗通常需要技能和经验,患者应转诊至具有专业知识的更大容量的机构[9];其次,CT扫描、PET-CT和任何进一步分析,都应根据解剖学和肿瘤学特征逐一进行;最后,应详细研究肺和心脏功能。

总之,T4期NSCLC的管理需要多学科和多模态检查,以决定更好的、更正确的治疗方法。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Fabio Davoli, Sai Yendamuri) for the series “Extended Pulmonary Resections for T4 Non-Small-Cell-Lung-Cancer” published in Journal of Xiangya Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jxym.2018.07.03). The series “Extended Pulmonary Resections for T4 Non-Small-Cell-Lung-Cancer” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Rami-Porta R, Bolejack V, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the Revisions of the T Descriptors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:990-1003.

- Farjah F, Wood DE, Varghese TK, et al. Trends in the operative management and outcomes of T4 lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:368-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yildizeli B, Dartevelle PG, Fadel E, et al. Results of primary surgery with T4 non-small cell lung cancer during a 25-year period in a single center: the benefit is worth the risk. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;86:1065-75; discussion 1074-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farjah F, Flum DR, Ramsey SD, et al. Multi-modality mediastinal staging for lung cancer among medicare beneficiaries. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:355-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silvestri GA, Gonzalez AV, Jantz MA, et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e211S-50S.

- Ohno Y, Koyama H, Lee HY, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET)/MRI for Lung Cancer Staging. J Thorac Imaging 2016;31:215-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Cassivi SD, Fibla J, et al. External validation of the recalibrated thoracic revised cardiac risk index for predicting the risk of major cardiac complications after lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:445-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999;100:1043-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Kim AW, Berger KI, et al. Physiologic evaluation of the patient with lung cancer being considered for resectional surgery: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e166S-90S.

- Berry MF, Villamizar-Ortiz NR, Tong BC, et al. Pulmonary function tests do not predict pulmonary complications after thoracoscopic lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:1044-51; discussion 51-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Little L, Rizzo L, et al. Diffusing capacity predicts morbidity and mortality after pulmonary resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1988;96:894-900. [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Refai MA, Salati M, et al. Carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity improves risk stratification in patients without airflow limitation: evidence for systematic measurement before lung resection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:567-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Vigneswaran WT. Diffusing capacity predicts morbidity after lung resection in patients without obstructive lung disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1158-64; discussion 64-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferguson MK, Reeder LB, Mick R. Optimizing selection of patients for major lung resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;109:275-81; discussion 81-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rivera MP, Detterbeck FC, Socinski MA, et al. Impact of preoperative chemotherapy on pulmonary function tests in resectable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2009;135:1588-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Margaritora S, Cesario A, Cusumano G, et al. Is pulmonary function damaged by neoadjuvant lung cancer therapy? A comprehensive serial time-trend analysis of pulmonary function after induction radiochemotherapy plus surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:1457-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melloul E, Egger B, Krueger T, et al. Mortality, complications and loss of pulmonary function after pneumonectomy vs. sleeve lobectomy in patients younger and older than 70 years. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008;7:986-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A, Xiumé F, Refai M, et al. Evaluation of expiratory volume, diffusion capacity, and exercise tolerance following major lung resection: a prospective follow-up analysis. Chest 2007;131:141-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brunelli A. Preoperative functional workup for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:S840-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amar D, Burt ME, Roistacher N, et al. Value of perioperative Doppler echocardiography in patients undergoing major lung resection. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;61:516-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rivera MP, Mehta AC, Wahidi MM. Establishing the diagnosis of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e142S-65S.

- Schreiber G, McCrory DC. Performance characteristics of different modalities for diagnosis of suspected lung cancer: summary of published evidence. Chest 2003;123:115S-28S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta A, Jain P, Minai OA, et al. Utility of transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of endobronchial lesions. Chest 1999;115:1237-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cox ID, Bagg LR, Russell NJ, et al. Relationship of radiologic position to the diagnostic yield of fiberoptic bronchoscopy in bronchial carcinoma. Chest 1984;85:519-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eberhardt R, Anantham D, Ernst A, et al. Multimodality bronchoscopic diagnosis of peripheral lung lesions: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:36-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trkanjec JT, Peros-Golubicić T, Grozdek D, et al. The role of transbronchial lung biopsy in the diagnosis of solitary pulmonary nodule. Coll Antropol 2003;27:669-75. [PubMed]

- Bandoh S, Fujita J, Tojo Y, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and safety of flexible bronchoscopy with multiplanar reconstruction images and ultrafast Papanicolaou stain: evaluating solitary pulmonary nodules. Chest 2003;124:1985-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steinfort DP, Khor YH, Manser RL, et al. Radial probe endobronchial ultrasound for the diagnosis of peripheral lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2011;37:902-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gildea TR, Mazzone PJ, Karnak D, et al. Electromagnetic navigation diagnostic bronchoscopy: a prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;174:982-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahajan AK, Patel S, Hogarth DK, et al. Electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy: an effective and safe approach to diagnose peripheral lung lesions unreachable by conventional bronchoscopy in high-risk patients. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2011;18:133-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zarbo RJ, Fenoglio-Preiser CM. Interinstitutional database for comparison of performance in lung fine-needle aspiration cytology. A College of American Pathologists Q-Probe Study of 5264 cases with histologic correlation. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1992;116:463-70. [PubMed]

- Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, et al. Population-based risk for complications after transthoracic needle lung biopsy of a pulmonary nodule: an analysis of discharge records. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:137-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eren S, Karaman A, Okur A. The superior vena cava syndrome caused by malignant disease. Imaging with multi-detector row CT. Eur J Radiol 2006;59:93-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dartevelle PG, Mitilian D, Fadel E. Extended surgery for T4 lung cancer: a 30 years' experience. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;65:321-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Lv P, Yang S, et al. Assessment of thoracic vasculature in patients with central bronchogenic carcinoma by unenhanced magnetic resonance angiography: comparison between 2D free-breathing TrueFISP, 2D breath-hold TrueFISP and 3D respiratory-triggered SPACE. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:1624-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohno Y, Nishio M, Koyama H, et al. Journal Club: Comparison of assessment of preoperative pulmonary vasculature in patients with non-small cell lung cancer by non-contrast- and 4D contrast-enhanced 3-T MR angiography and contrast-enhanced 64-MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014;202:493-506. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohno Y, Adachi S, Motoyama A, et al. Multiphase ECG-triggered 3D contrast-enhanced MR angiography: utility for evaluation of hilar and mediastinal invasion of bronchogenic carcinoma. J Magn Reson Imaging 2001;13:215-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell JD, Mathisen DJ, Wright CD, et al. Resection for bronchogenic carcinoma involving the carina: long-term results and effect of nodal status on outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;121:465-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marulli G, Rendina EA, Klepetko W, et al. Surgery for T4 lung cancer invading the thoracic aorta: Do we push the limits? J Surg Oncol 2017;116:1141-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Misthos P, Papagiannakis G, Kokotsakis J, et al. Surgical management of lung cancer invading the aorta or the superior vena cava. Lung Cancer 2007;56:223-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stella F, Dell'Amore A, Caroli G, et al. Surgical results and long-term follow-up of T(4)-non-small cell lung cancer invading the left atrium or the intrapericardial base of the pulmonary veins. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;14:415-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galvaing G, Tardy MM, Cassagnes L, et al. Left atrial resection for T4 lung cancer without cardiopulmonary bypass: technical aspects and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:1708-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waseda R, Klikovits T, Hoda MA, et al. Trimodality therapy for Pancoast tumors: T4 is not a contraindication to radical surgery. J Surg Oncol 2017;116:227-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reed CE, Harpole DH, Posther KE, et al. Results of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0050 trial: the utility of positron emission tomography in staging potentially operable non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;126:1943-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio RJ, Ojha B, Bryant AS, et al. The role of FDG-PET scan in staging patients with nonsmall cell carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:861-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Leyn P, Dooms C, Kuzdzal J, et al. Revised ESTS guidelines for preoperative mediastinal lymph node staging for non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:787-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu LM, Xu JR, Gu HY, et al. Preoperative mediastinal and hilar nodal staging with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: which is better? J Surg Res 2012;178:304-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:568-77.

- Liberman M, Sampalis J, Duranceau A, et al. Endosonographic mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer. Chest 2014;146:389-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Micames CG, McCrory DC, Pavey DA, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for non-small cell lung cancer staging: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest 2007;131:539-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gu P, Zhao YZ, Jiang LY, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:1389-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams K, Shah PL, Edmonds L, et al. Test performance of endobronchial ultrasound and transbronchial needle aspiration biopsy for mediastinal staging in patients with lung cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2009;64:757-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chandra S, Nehra M, Agarwal D, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy in mediastinal lymphadenopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care 2012;57:384-91. [PubMed]

- Zhang R, Ying K, Shi L, et al. Combined endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for mediastinal lymph node staging of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1860-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tournoy KG, De Ryck F, Vanwalleghem LR, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound reduces surgical mediastinal staging in lung cancer: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:531-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vilmann P, Clementsen PF, Colella S, et al. Combined endobronchial and oesophageal endosonography for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline, in cooperation with the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur Respir J 2015;46:40-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hürtgen M, Friedel G, Toomes H, et al. Radical video-assisted mediastinoscopic lymphadenectomy (VAMLA)--technique and first results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;21:348-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuzdzał J, Zieliński M, Papla B, et al. Transcervical extended mediastinal lymphadenectomy--the new operative technique and early results in lung cancer staging. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;27:384-90; discussion 90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rami-Porta R, Call S. Invasive staging of mediastinal lymph nodes: mediastinoscopy and remediastinoscopy. Thorac Surg Clin 2012;22:177-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Cabanyes Candela S, Detterbeck FC. A systematic review of restaging after induction therapy for stage IIIa lung cancer: prediction of pathologic stage. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:389-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Bartheld MB, Versteegh MI, Braun J, et al. Transesophageal ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for the mediastinal restaging of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1510-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Leyn P, Lardinois D, Van Schil PE, et al. ESTS guidelines for preoperative lymph node staging for non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lardinois D, Schallberger A, Betticher D, et al. Postinduction video-mediastinoscopy is as accurate and safe as video-mediastinoscopy in patients without pretreatment for potentially operable non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:1102-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Xu W, Kong F, et al. Meta-analysis: accuracy of 18FDG PET-CT for distant metastasis staging in lung cancer patients. Surg Oncol 2013;22:151-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohno Y, Koyama H, Onishi Y, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: whole-body MR examination for M-stage assessment--utility for whole-body diffusion-weighted imaging compared with integrated FDG PET/CT. Radiology 2008;248:643-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu GZ, Li CY, Zhao L, et al. Comparison of FDG whole-body PET/CT and gadolinium-enhanced whole-body MRI for distant malignancies in patients with malignant tumors: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol 2013;24:96-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Na II, Lee TH, Choe DH, et al. A diagnostic model to detect silent brain metastases in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:2411-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

王琼

中国人民解放军总医院第一医学中心病理科,副主任技师,病理与病理生理学博士,兼任《中华生物医学工程杂志》《中华病理学杂志》等杂志审稿人。参与省部级以上课题3项,获实用新型专利3项,发表多篇SCI论文、中文文章。(更新时间:2021/9/13)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Viti A, Bertoglio P, Terzi AC. Diagnosis and staging of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Xiangya Med 2018;3:32.