综述——术后谵妄的诊断和处理策略

背景

谵妄由来已久,最早可追溯至公元1世纪的医学文献[1]。这一术语来源于拉丁文“delirare”,意为“偏离犁沟”[2,3]。用农业术语来说,谵妄患者偏离了本该犁开的直路。尽管人们对谵妄状态认知已久,但其确切病因和最佳治疗措施仍不明确。过去的20年,医学专家们开始努力探索谵妄的奥秘,但很多医疗机构仍然对谵妄诊断不足且治疗不善。有数据表明谵妄是老年患者最常见的术后神经系统并发症[4]。因此,临床医生必须更加熟练地预防和处理谵妄,以改善患者术后预后。

POD之所以容易发生误诊且缺少有效的治疗,其原因包括对患者院前认知功能了解不足、主观认定老年患者的意识障碍是正常生理表现,或仅仅是没有将谵妄纳入鉴别诊断。POD的漏诊和不当治疗会给患者带来严重危害。有明确数据表明谵妄导致死亡率提高、住院时间延长、住院率提高、患者机能下降[5-12]。因此,医务人员必须加深对POD的理解,并采取有效措施降低POD的发生率,缓解其对患者的不良影响。

谵妄的定义

世界卫生组织(World Health Organization, WHO)将谵妄定义为“一种无特定病因的器质性脑综合征,其特征是意识、注意力、感知、思维、记忆、精神运动行为、情感和睡眠觉醒障碍,持续时间不定,严重程度不等”[13]。美国精神病学协会在第五版《诊断与统计手册》(Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-V, DSM-V)中提出了类似的定义,DSM-V中,谵妄的的诊断标准包括无诱因的注意力障碍、认知障碍和认知水平急性改变[14]。

谵妄通常有两种主要类型:活跃型和减退型。活跃型通常很容易识别,此类患者容易激动,有攻击性,拒绝与医务人员合作,可能会四处踱步,拔出静脉置管、导管或插管。此外,活跃型谵妄患者多出现幻视,较少出现幻听和妄想[2,15],这些幻觉和妄想会给患者和家属造成巨大的痛苦,尤其当患者认为医务人员试图伤害他/她时。即使在经过治疗消除谵妄之后,一些患者仍然认为护士或医生想要伤害或毒害他们,从而发生创伤后应激障碍(post-traumatic stress disorder,PTSD)[16]。

与活跃型谵妄相比,减退型谵妄的特征是精神运动减少,患者常嗜睡,也可能表现为抑郁。当他们听到有人呼唤他们的名字时会醒来,但又很快睡着。这类患者也会感到困惑,但这种困惑并不明显,只有在检查患者的注意力和思维过程时才会发现。不幸的是,减退型谵妄通常会被忽略,尤其是在老年患者中,并且减退型谵妄往往伴随不良预后[2,15]。

谵妄的第三种类型是混合型,表现为活跃和减退症状同时存在或交替发生。

谵妄具有波动性,记住这一点很重要,经常会出现护士发现患者精神状态异常之后报告给医生,但当医生到达床旁时,患者已经好转的情况。躁动往往在夜间加重,因此白天的治疗团队可能从未亲眼目睹患者病历上记录的夜间异常行为[17]。

病理生理学

谵妄的发生机制仍不明确。人们普遍认为谵妄是患者本身的脆弱性或危险因素与外界应激源(如感染、手术)共同作用的结果[11,15]。神经递质失衡(尤其是胆碱能缺乏)、炎症、电解质或代谢紊乱等是谵妄发生的应激源[18]。由于谵妄的病理生理学机制仍未明确,识别已知且可干预的危险因素至关重要。

危险因素

有研究表明,谵妄是可以预防的[19]。因此,在择期手术前应了解患者的危险因素,以便采取措施对患者进行干预,以期减少POD的发生率[2]。尽管研究对象的来源不同,危险因素也会有所不同,但结果显示患者潜在的认知功能障碍是谵妄发生的最大危险因素[5]。最近的几项研究着眼于心脏和非心脏手术后谵妄的危险因素(表1),两种手术患者POD的共同危险因素是高龄、认知障碍、白蛋白减少和体重减轻[5,20-25]。

Full table

值得注意的是,与传统股动脉入路相比,在经导管主动脉瓣置换术(transcatheter aortic valve replacement, TAVR)中使用非股动脉入路(经心尖或经主动脉),谵妄发生率更高,所以在手术入路选择方面,应尽量避免非股动脉入路[22,25]。

英国国家健康和临床优化研究所(National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence’s,NICE)的指南表明,年龄>65岁、有认知障碍,以及患有严重疾病或髋部骨折的患者发生POD的风险增加[16]。美国老年医学学会(American Geriatrics Society,AGS)提出了POD的22个危险因素,并指出同时具有2个及以上危险因素的患者发生POD的风险较高[16]。

风险预测模型

POD的风险预测模型很多,最著名的模型之一是Marcantonio等人提出的针对择期非心脏手术患者的模型。该模型的危险因素包括年龄>70岁、酗酒、认知状态电话采访得分<30分、严重身体损害(特殊活动量表IV级)、电解质显著异常、主动脉瘤手术和非心胸外科手术。主动脉瘤手术积2分,其他危险因素均积1分。得分为1~2分的患者POD发生率为11%,得分≥3分的患者POD发生率为50%[11]。

Rudolph等人设计了一个心脏手术的POD预测模型。在该模型中,既往脑卒中或短暂性脑缺血发作(transient ischemic attack,TIA)、白蛋白异常(<3.5 g/dL或>4.5 g/dL)、老年抑郁症评分>4分各积1分。如果患者的简易精神状态检查(mini mental state examination,MMSE)得分为24~27分,加1分;若MMSE得分≤23分,则加2分。使用该模型,得1分者POD风险为43%,得2分者POD风险为60%,≥3分者POD风险为87%[26]。

Inouye等人也发表了一种用于普通患者的谵妄预测模型,用于评估患者的视力损害、认知障碍、严重疾病和高血尿素氮/肌酐比。若患者同时有3~4个危险因素,发生院内谵妄的概率为83%[27]。

结局事件

认知结局事件

有充分证据表明,谵妄对认知功能有长期不良影响[28-30]。Levkoff等报道在出院后6个月内,仅17.7%谵妄患者的注意力涣散和方向感障碍等症状会完全消失[28]。2012年,Saczynski等学者的研究表明,谵妄患者术后6个月较难恢复到术前认知基线水平。事实上,无谵妄患者的认知水平通常在术后1个月内恢复,而谵妄患者术后1年的认知水平仍低于基线水平[29]。

绝大多数老年病专家认为谵妄与痴呆之间存在关联。一项研究发现,心脏手术后,87%的痴呆患者都曾经历过POD[31]。另外两项研究通过对患者进行长达4年的随访,发现既往有谵妄的患者痴呆发生率增加(62.5% vs 8.1%)[12]。

这是个“先有鸡还是先有蛋”的问题,谵妄是痴呆的早期征兆?还是谵妄本身导致痴呆?最近的研究表明,谵妄可能与痴呆有多种联系。谵妄可能提示了大脑的脆弱性,也可能是此前未记录在案的痴呆的首发症状,并因此造成神经元损伤,继而导致痴呆[32]。

住院率增加

谵妄患者在出院时和出院后6个月内需要更多的日常生活活动能力(activities of daily living,ADLs)帮助[10]。具备完全胜任日常生活活动的能力是安全出院的标准,因此许多谵妄患者出院后会去护理机构或接受长期护理。一项针对择期非心脏手术患者的研究发现,36%的谵妄患者被送至护理机构,而在无谵妄患者中,这一比例仅为11%[11]。最近一篇纳入7项研究的Meta分析也表明谵妄患者的住院风险增加了3倍以上(33.4% vs 10.7%)[12]。

住院时间延长

在医疗系统中,报销基于诊断而非住院天数和医疗服务,住院时间延长会导致重大经济损失,而谵妄患者的住院时间可能增加1倍以上[11]。此外,住院时间延长会增加医疗过失、感染、身体状况恶化的风险。

术前筛查的重要性

AGS最佳实践指南建议,手术患者应进行术前评估,以寻找谵妄的危险因素[33]。大不列颠和爱尔兰麻醉师协会也建议在对老年患者实施麻醉前进行谵妄风险评估[16]。

如果将POD视为急性脑衰竭的一种形式,那么很显然,它是住院患者的重要并发症之一。因此,让患者意识到POD的风险是很重要的,这也是知情同意的一部分[16]。除了法律原因外,手术前向患者及家属解释谵妄风险也有助于他们更好应对POD[34]。

在术前风险评估时,医务人员应清晰记录患者目前的认知状况和ADLs执行能力[33,35]。此外,应进行视觉和听觉评估,并告知患者携带眼镜或助听器入院的重要性[35]。许多患者和家属担心在医院丢失昂贵的视听觉辅助设备,因此将这些设备留在家中,所以医务人员必须说明这些设备在感官优化和谵妄预防方面的价值。

诊断

除了使用WHO和AGS的定义之外,还有多种工具可以帮助诊断谵妄。

研究中最常用的筛查工具是意识模糊评估法(confusion assessment method,CAM),较之于精神科医师的谵妄诊断标准,CAM的敏感性和特异性较高(90%~100%)[36]。CAM有多个版本,包括10节的完整版和4节的简略版。完整版通常在研究中使用,简略版通常在临床实践中使用。简略版评估患者的4个方面:敏锐度/波动、注意力、思维、意识水平。与其他筛查工具相比,CAM也是住院时间延长和死亡率的最佳预测工具[37]。一篇基于25项前瞻性研究的系统综述回顾了床旁试验在谵妄评估中的效用,作者得出结论:尽管有多种选择,但使用CAM的证据最佳,CAM通常可以在5分钟或更短的时间内完成[38]。

另一种筛查工具称为重症监护谵妄筛查清单(Intensive care delirium screening checklist,ICDSC)。ICDSC评估8个指标:意识水平、注意力、方向感、幻觉/妄想、精神运动功能变化、不恰当言语或情绪、睡眠-觉醒障碍、症状波动[39]。一项基于4个ICDSC准确性研究的Meta分析结果表明ICDSC的综合敏感性为74%,综合特异性为81.9%[40]。

4AT是一种新的谵妄筛查工具,当医生时间有限时,这种筛查方案可能独具优势。这一工具评估谵妄的4个特征:警觉性、方向感、注意力、急性变化或病程波动。与老年医学诊断相比,4AT诊断的敏感性为89.7%,特异性为84.1%[41]。

尽管这些筛查工具多数都简短易行,但一些医生仍觉得它们很费时间。在这种情况下,我们建议评估患者的方向感并要求他们执行注意力任务[18]。注意力任务建议包括“100-7”(允许错1个),或倒序说出一周的星期名(不允许出错),或倒序说出一年的月份(允许错1个)[15,18,35]。

患者被诊断为谵妄后,可以使用其他工具如记忆性谵妄评估量表(memorial delirium assessment scale,MDAS)来确定谵妄的严重程度。MDAS使用10个条目评估谵妄特征,包括意识、方向感、短期记忆、注意力、思维紊乱、精神运动活动变化、睡眠障碍[42]。MDAS确定的严重程度与结局事件有关,谵妄越严重,住院率和6个月死亡率越高[43]。

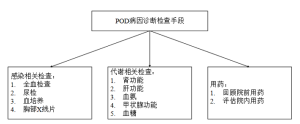

检查

患者一旦确诊为谵妄,最重要的是寻找导致POD的原因。图1是POD病因推断流程,可以通过几种检查方式来寻找病原体:全血检查、尿检、血培养、胸部X线片。其他检查包括肝肾功能、血氨水平、甲状腺功能、血糖水平[2,44]。

还应仔细检查患者院前、院内的用药情况[2,35]。抗组胺药、苯二氮卓类、阿片类、抗胆碱能药物都是谵妄的诱因[45,46],要了解患者的用药依从性,以及是否正在服用其他处方或补充剂。还应询问其饮酒史,因为酒精和苯二氮卓类药物戒断均可导致谵妄。

谵妄的原因很多,医生应努力治疗所有可能的原因,而不能局限于一种病因[15,35]。

神经成像(CT、MRI)对谵妄诊断的指导作用很小,除非患者有局灶性神经缺陷。腰椎穿刺也不应常规使用,除非强烈怀疑脑膜炎[2]。

管理策略

老年咨询

老年科医生接受过谵妄管理培训,因此,医院已逐步运用老年咨询顾问协助或共同管理老年外科患者的方式,旨在减少谵妄的发生率和后遗症。在一项研究中,在术前或术后24h内对髋部骨折患者进行老年咨询,由老年科医生诊治的患者谵妄明显减少(32% vs 50%常规护理)[47]。Wang等的一项Meta分析也发现,接受综合老年护理的患者POD发生率更低,术后认知状态更佳[48]。

多因素干预

谵妄是由多种因素引起的,因此,与常规护理相比,多因素干预可降低谵妄发生率[19,49]。最成功的多因素干预方案之一是医院老年生活计划(hospital elder life program,HELP)。HELP标准化方案针对6个危险因素(认知障碍、睡眠剥夺、行动不便、视觉障碍、听觉障碍、脱水)预防谵妄并改善整体护理[19]。多因素干预可降低40%的谵妄发生率,但对谵妄的严重程度无影响[19]。这种干预方法需要多学科团队,每预防1例谵妄的花费约为6000美元[19]。这一方案的成本之高可能会令很多医疗机构望而却步,但如果考虑到每例谵妄患者的医疗费用为16 000~64 000美元/年,多因素干预实际上能节省费用[50]。

2010年,NICE发布了谵妄的预防和管理推荐,该指南扩展了HELP标准化方案,建议患者入院时进行谵妄风险评估,注意评估认知障碍、脱水或便秘、缺氧、行动不便、感染、药物使用、疼痛、营养不良、感觉减退、睡眠障碍等因素[51]。

麻醉

麻醉的实施与老年人谵妄和认知能力下降有关[30]。有人建议使用局部麻醉代替全身麻醉,但2016年一篇基于18项随机对照试验的综述并未显示2种麻醉方式间谵妄发生率有显著差异[52]。一项基于2个研究的Meta分析表明,双频谱指数(bispectral index,BIS)引导下麻醉可降低谵妄发生率[49]。

疼痛管理

围术期疼痛很难控制,因为疼痛本身和阿片类药物都会导致谵妄,建议老年人考虑长期疼痛治疗。对乙酰氨基酚1 000mg,3次/d,既能减轻疼痛,又能减少对强效镇痛药物的需求[33,35]。

抗精神病药物

美国食品药品监督管理局(Food and Administration,FDA)尚未批准任何抗精神病药物用于谵妄的治疗,但当非药物治疗无法阻止患者伤害自己或他人时,抗精神病药物会经常使用[53]。虽然氟哌啶醇是最常用的抗精神病药物,但许多非典型抗精神病药物也有类似的药性,并且对谵妄同样有效[54]。尽管口服氟哌啶醇对QTc的影响相当小(<8ms),仍然建议对患者的QTc进行心电图监测[53]。

虽然抗精神病药物可用于治疗谵妄,但它们能否预防POD尚不清楚[15]。2012年的一项研究表明,在非心脏手术患者中预防性使用氟哌啶醇可减少POD发生[55]。然而,多项对老年髋关节手术患者预防性使用氟哌啶醇的研究并未显示氟哌啶醇具有降低谵妄发生率的作用[56,57]。

人们一致认为,谵妄消退时应立即停用抗精神病药物,或在3~5天内停用[2,44,53]。但许多患者出院后仍在服用这些药物,随机抽取300例住院期间服用过抗精神病药物的老年患者,48%的患者出院时仍在服用这类药物[58]。在患者出院前进行用药比对,使其停用抗精神病药物,或在护理过渡期间与患者进行明确沟通并指导如何减药,对于患者来说是至关重要的。

苯二氮卓类药物

由于苯二氮卓类药物会导致谵妄,因此,除特殊情况外,不建议将其作为谵妄的治疗药物[59]。苯二氮卓类药物适用于因酒精或镇静戒断而发生谵妄的患者,也用于路易体痴呆或帕金森病的患者,因为这类患者具有神经安定药敏感性[2,59],且最好使用小剂量的速效药物,如劳拉西泮[2]。平常规律服用苯二氮卓类药物的患者在围术期应继续服用,可减量,以防戒断性谵妄。对于无法口服药物的患者,可使用苯二氮卓类静脉制剂。

氯胺酮

基于氯胺酮可有效减少儿童谵妄的研究,一些研究着眼于在术中使用氯胺酮,以预防老年人POD。但这类文献较为缺乏,且结论多有矛盾[60,61]。目前不推荐使用氯胺酮预防谵妄,并且氯胺酮会导致幻觉和梦魇增加[61]。

右美托咪定

近年来α2-肾上腺素能受体激动剂右美托咪定在ICU被广泛使用。右美托咪定可降低谵妄发生率、减少阿片类药物的使用[62]。右美托咪定可减少心脏和非心脏手术患者的谵妄,中国最近的一项研究显示,围术期接受静脉输注右美托咪定的非心脏手术患者POD发生率显著降低(9% vs 23%)[63]。一项基于8个随机对照试验的Meta分析表明,与心脏术后使用丙泊酚相比,使用右美托咪定的患者谵妄发生风险降低。但右美托咪定可导致心动过缓,可能不适用于心脏病患者[64]。虽然术后右美托咪定给药似乎可降低谵妄发生率,但术中给药无显著益处[62]。

褪黑素

鉴于谵妄患者的睡眠周期紊乱,学界对使用褪黑素治疗谵妄寄予厚望。日本最近的一项随机对照试验表明,预防性服用褪黑素激动剂雷美替胺(Ramelteon)可降低谵妄发生率[65]。然而,一篇基于4项研究的Meta分析表明,使用褪黑素预防谵妄的结果有好有坏。一项亚组分析显示,在普通外科患者中,褪黑素可使谵妄发生率降低75%,但在所有手术患者中,谵妄发生率并未降低[66]。另一篇基于3项研究的综述发现,没有明确证据表明使用褪黑素或褪黑素激动剂可降低谵妄发生率[49]。相比褪黑素而言,更建议使用非药物助眠方式,如热饮、冥想、轻松的音乐、背部按摩等[15]。

随访

NICE的最后一个建议是对有谵妄病史的患者进行老年医学团队随访。考虑到谵妄与痴呆和其他不良结局的关联,老年医学团队随访可能有助于患者及家属识别和处理后遗症,并有望降低未来发生谵妄的风险[2]。

结论

POD是医务人员和外科患者,特别是老年外科患者面临的重大问题。尽管这种疾病已为人们所熟知,但人们对其病理生理学仍然知之甚少,也没有特殊的治疗方法。很明显,术前评估可以识别POD的危险因素。确定可干预和不可干预的危险因素至关重要,有助于采取措施,以减少谵妄的发生。术前识别谵妄的危险因素可让患者了解他们发生谵妄的风险,这是知情同意的一部分。在医院内,多种有效工具可帮助诊断谵妄。预防是最好的治疗,一旦发生谵妄,老年咨询和多因素干预都是有效的方案。尽管抗精神病药被常规用于治疗谵妄,但目前尚无药物治疗方案可纠正谵妄。鉴于谵妄相关的不良结局,研究人员需要继续努力寻找谵妄的最佳防治策略。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Moises Auron, Christopher Whinney) for the series “Update in Perioperative Medicine” published in Journal of Xiangya Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jxym.2018.01.03). The series "Update in Perioperative Medicine" was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Adamis D, Treloar A, Martin FC, et al. A brief review of the history of delirium as a mental disorder. Hist Psychiatry 2007;18:459-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saxena S, Lawley D. Delirium in the elderly: a clinical review. Postgrad Med J 2009;85:405-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dictionary OE. Delirium. Oxford English Dictionary 2014.

- Sieber FE, Barnett SR. Preventing postoperative complications in the elderly. Anesthesiol Clin 2011;29:83-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson TN, Raeburn CD, Tran ZV, et al. Postoperative delirium in the elderly: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Surg 2009;249:173-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi N, House AO, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing 2006;35:350-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McAvay GJ, Van Ness PH, Bogardus ST Jr, et al. Older adults discharged from the hospital with delirium: 1-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1245-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Pan L, Ni H. Impact of delirium on clinical outcome in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:105-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin SM, Huang CD, Liu CY, et al. Risk factors for the development of early-onset delirium and the subsequent clinical outcome in mechanically ventilated patients. J Crit Care 2008;23:372-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quinlan N, Rudolph JL. Postoperative delirium and functional decline after noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:S301-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA 1994;271:134-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, et al. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;304:443-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Organization WH. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). Available online: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en

- Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. Available online: http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleID=158714%5Cn

- Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:210-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson JH, Partridge JS. Preoperative discussion with patients about delirium risk: are we doing enough? Perioper Med (Lond) 2016;5:22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown TM, Boyle MF. Delirium. BMJ 2002;325:644-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014;383:911-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med 1999;340:669-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cereghetti C, Siegemund M, Schaedelin S, et al. Independent Predictors of the Duration and Overall Burden of Postoperative Delirium After Cardiac Surgery in Adults: An Observational Cohort Study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:1966-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Soundhar A, Udesh R, Mehta A, et al. Delirium Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: National Inpatient Sample Analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:1977-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abawi M, Nijhoff F, Agostoni P, et al. Incidence, Predictive Factors, and Effect of Delirium After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2016;9:160-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neerland BE, Krogseth M, Juliebø V, et al. Perioperative hemodynamics and risk for delirium and new onset dementia in hip fracture patients; A prospective follow-up study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180641. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin Y, Chen J, Wang Z. Meta-analysis of factors which influence delirium following cardiac surgery. J Card Surg 2012;27:481-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bagienski M, Kleczynski P, Dziewierz A, et al. Incidence of Postoperative Delirium and Its Impact on Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am J Cardiol 2017;120:1187-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation 2009;119:229-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inouye SK, Viscoli CM, Horwitz RI, et al. A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:474-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levkoff SE. Delirium. Archives of Internal Medicine 1992;152.

- Saczynski JS, Marcantonio ER, Quach L, et al. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med 2012;367:30-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, et al. Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet 1998;351:857-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lingehall HC, Smulter NS, Lindahl E, et al. Preoperative Cognitive Performance and Postoperative Delirium Are Independently Associated With Future Dementia in Older People Who Have Undergone Cardiac Surgery: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Crit Care Med 2017;45:1295-303. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fong TG, Davis D, Growdon ME, et al. The interface between delirium and dementia in elderly adults. The Lancet Neurology 2015;14:823-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Postoperative Delirium in Older Adults. Postoperative delirium in older adults: best practice statement from the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg 2015;220:136-48.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Partridge JS, Martin FC, Harari D, et al. The delirium experience: what is the effect on patients, relatives and staff and what can be done to modify this? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2013;28:804-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rudolph JL, Marcantonio ER. Review articles: postoperative delirium: acute change with long-term implications. Anesth Analg 2011;112:1202-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:941-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tomasi CD, Grandi C, Salluh J, et al. Comparison of CAM-ICU and ICDSC for the detection of delirium in critically ill patients focusing on relevant clinical outcomes. J Crit Care 2012;27:212-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Simel DL, et al. Does this patient have delirium?: value of bedside instruments. JAMA 2010;304:779-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, et al. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:859-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gusmao-Flores D, Salluh JI, Chalhub RA, et al. The confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) and intensive care delirium screening checklist (ICDSC) for the diagnosis of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Crit Care 2012;16:R115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DH, et al. Validation of the 4AT, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: a study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age Ageing 2014;43:496-502. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Roth A, et al. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;13:128-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marcantonio E, Ta T, Duthie E, et al. Delirium severity and psychomotor types: their relationship with outcomes after hip fracture repair. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:850-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reuben DB HKP. Delirium. Geriatrics at Your Fingertips. Massachusetts: Blackwell Science, 2002.

- By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2227-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alagiakrishnan K, Wiens CA. An approach to drug induced delirium in the elderly. Postgrad Med J 2004;80:388-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, et al. Reducing Delirium After Hip Fracture: A Randomized Trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2001;49:516-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Tang J, Zhou F, et al. Comprehensive geriatric care reduces acute perioperative delirium in elderly patients with hip fractures: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7361. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi N, Harrison JK, Clegg A, et al. Interventions for preventing delirium in hospitalised non-ICU patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD005563. [PubMed]

- Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, et al. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:27-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yue J, Tabloski P, Dowal SL, et al. NICE to HELP: operationalizing National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines to improve clinical practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:754-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bryson GL, Wyand A. Evidence-based clinical update: general anesthesia and the risk of delirium and postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Can J Anaesth 2006;53:669-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thom RP, Mock CK, Teslyar P. Delirium in hospitalized patients: Risks and benefits of antipsychotics. Cleve Clin J Med 2017;84:616-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lonergan E, Britton AM, Luxenberg J, et al. Antipsychotics for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;CD005594. [PubMed]

- Wang W, Li HL, Wang DX, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis decreases delirium incidence in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial*. Crit Care Med 2012;40:731-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, Bogaards MJ, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1658-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vochteloo AJ, Moerman S, van der Burg BL, et al. Delirium risk screening and haloperidol prophylaxis program in hip fracture patients is a helpful tool in identifying high-risk patients, but does not reduce the incidence of delirium. BMC Geriatr 2011;11:39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loh KP, Ramdass S, Garb JL, et al. From hospital to community: use of antipsychotics in hospitalized elders. J Hosp Med 2014;9:802-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aarsland D, Perry R, Larsen JP, et al. Neuroleptic sensitivity in Parkinson's disease and parkinsonian dementias. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:633-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hudetz JA, Patterson KM, Iqbal Z, et al. Ketamine attenuates delirium after cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2009;23:651-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Avidan MS, Maybrier HR, Abdallah AB, et al. Intraoperative ketamine for prevention of postoperative delirium or pain after major surgery in older adults: an international, multicentre, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2017;390:267-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deiner S, Luo X, Lin HM, et al. Intraoperative Infusion of Dexmedetomidine for Prevention of Postoperative Delirium and Cognitive Dysfunction in Elderly Patients Undergoing Major Elective Noncardiac Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2017;152:e171505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Su X, Meng Z-T, Wu X-H, et al. Dexmedetomidine for prevention of delirium in elderly patients after non-cardiac surgery: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2016;388:1893-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Xie G, Zhang K, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs propofol sedation reduces delirium in patients after cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Crit Care 2017;38:190-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hatta K, Kishi Y, Wada K, et al. Preventive effects of ramelteon on delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:397-403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen S, Shi L, Liang F, et al. Exogenous Melatonin for Delirium Prevention: a Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Mol Neurobiol 2016;53:4046-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

刘华

湖北省十堰市太和医院胸心大血管外科,副主任医师,博士研究生。中国医师协会腔内血管学专家委员会委员,湖北省微循环学会胸部微创青年委员会常务委员,湖北省医学会胸心外科学分会结构性心脏病专业委员会委员,十堰市医学会胸心大血管外科专业委员会委员,十堰市胸心大血管外科医疗质量控制委员会委员。从事心血管疾病的基础及临床研究,主持并完成湖北省厅级科研项目4项,获湖北省科学技术进步二等奖1项,发表科研论文20余篇。擅长心血管、胸部肿瘤及胸部创伤疾病的开放、胸腔镜及微创介入外科治疗。(更新时间:2021/9/2)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Cunningham J, Kim LD. Post-operative delirium: a review of diagnosis and treatment strategies. J Xiangya Med 2018;3:8.